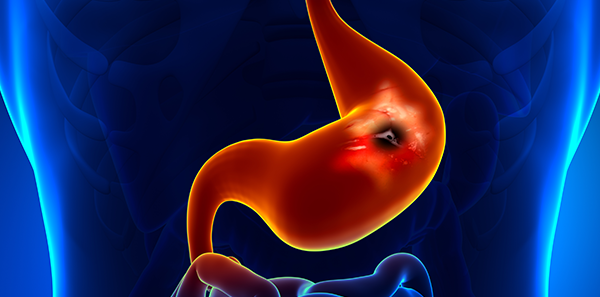

The human stomach is a very hostile environment for microorganisms. The stomach secretes large amounts of hydrochloric acid to digest food, so its PH is usually lower than two.

Even so, there is a bacterium that manages to live in this hostile environment. It is called Helicobacter pylori, and you have most likely heard of it. It is a spiroidal bacillus and a flagellum that enables it to quickly penetrate the mucous that lines the stomach. It produces large amounts of an alkalising enzyme called urease that creates a non-acidic “microclimate” around it. H. Pylori was discovered in 1982 by researchers Warren and Marshall, who showed that this infection was responsible for gastric and duodenal ulcers rather than stress and lifestyle, as was thought at the time. They were severely criticised by their colleagues, but time proved them right, and they were finally honoured for their discovery with a Nobel Prize in 2005. The infection is transmitted from person to person through faeces, and the proportion of infected people grows with age. It is far more common in developing countries, where the rate of infection among the adult population exceeds 80%. In industrialised countries like ours, the infection rate is around 10% among adults aged 18 to 30, reaching 50 per cent among persons aged 60 years and over. Mere gastric colonization is not enough to cause disease.

There are other factors that depend on the host and the environment, and only 15-20% of those infected go on to develop symptoms related to H. pylori infection. H. pylori infection produces a type of gastritis called chronic active gastritis. This gastritis, in itself, does not cause any symptoms, at least in the majority of patients. However, the diseases related to H. pylori infection, which are duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, MALT-type gastric lymphoma and adenocarcinoma of the stomach, cause symptoms. When any of these diseases is diagnosed, the bacteria should be eradicated to avoid a relapse. There are other situations when patients should be tested for H. pylori and the bacteria should be eradicated if the patient has other factors that pose an increased risk of related diseases. One example would be the need for long-term treatment with aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), since these medicines can cause gastric or duodenal ulcers. Another would be increased risk in patients with a family history of gastric cancer and a high genetic burden of this disease. It is also worth mentioning functional dyspepsia. Patients who suffer from this disorder have intermittent or chronic symptoms that mimic peptic ulcer or gastric cancer, such as epigastric pain (pain in the pit of her stomach), feeling bloated after meals, heaviness, slow digestion or feeling full after eating small amounts of food.

The key to diagnosis is the existence of these symptoms and the absence of lesions in the stomach and duodenum, shown by a gastroscopy. This disorder is chronic and it does not respond well to treatment. The rate of H. pylori infection in patients with functional dyspepsia is the same as that of the general population, and in most cases the infection has no relation to the symptoms. However, about 10% of patients with functional dyspepsia and H. pylori infection may experience a prolonged improvement of symptoms if the infection is eradicated. Therefore, eradication treatment must be considered, at least in cases where the symptoms are intense and persistent. Diagnosis is easy with a breath test, stool analysis or gastroscopy, by taking samples of gastric mucosa. In all cases the patient must refrain from taking proton-pump inhibitors (Omeprazole and similar) for 2 weeks before the test, and all types of antibiotic for a month. Eradication treatment is based on a combination of strong antisecretory drugs and at least two antibiotics, taken simultaneously for 10 to 14 days. Of course, after an eradication treatment, it is important to check that the infection has been eliminated. There is a breath test for detecting H. pylori and it can also be detected in faeces, so an endoscopy is not required. With the current guidelines these bacteria are typically eradicated in more than 90% of patients who complete the treatment cycle. Once cured, reinfection is rare. The rate of reinfection after successful eradication is around one per cent per annum.

The information published in this media neither substitutes nor complements in any way the direct supervision of a doctor, his diagnosis or the treatment that he may prescribe. It should also not be used for self-diagnosis.

The exclusive responsibility for the use of this service lies with the reader.

ASSSA advises you to always consult your doctor about any issue concerning your health